The pandemic is causing massive disruptions to flows of foreign direct investments. Developing countries are likely to be hit the hardest.

COVID-19 is uprooting economic globalization. With both supply and demand experiencing simultaneous shocks due to containment measures, global production networks are being disrupted on a scale never witnessed before. The pandemic has exposed how globally interconnected the flow of goods and services has become, and countries are now rethinking their international trade strategies to reduce their vulnerability to global economic shocks.

Disruptions to flows of foreign direct investments (FDI) — which are part and parcel of economic globalization — are no exception. In late March, the International Monetary Fund announced that investors had removed 83 billion US$ from developing countries since the beginning of the COVID-19 crisis, the largest capital outflow ever recorded (IMF, 2020). According to the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), global FDI flows are expected to contract between 30 per cent to 40 per cent during 2020/21. All sectors will be affected, but sharp contractions in FDI are especially evident in consumer cyclicals, such as airlines, hotels, restaurants and leisure, as well as manufacturing industries and the energy sector (UNCTAD, 2020).

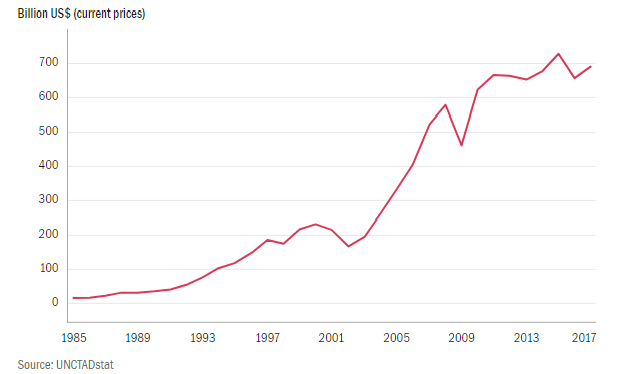

Figure 1: FDI inflows to developing countries

FDI inflows to developing countries are not uniform in either quantity or quality. Fast-growing economies in Asia with large populations have been driving the surge over the past few decades, most importantly China, but also Cambodia, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Thailand and Viet Nam (this is not to say that Latin America is irrelevant, where Brazil and Mexico account for a large share of FDI inflows into developing countries). The inflows of investments into these countries are mainly concentrated in manufacturing and services. If we look at dependence on FDI inflows rather than their quantity, African countries enter the picture. The FDI inflows to Africa tell a different story to those of developing countries in Asia. In Africa, the extractive industries, such as oil and mining, attract most FDI inflows. This type of direct investments tends to be more volatile, which explains the erratic swings in FDI inflows in the cases of Congo and Mozambique. Ethiopia is an exception with the growth in FDI inflows being largely concentrated in the manufacturing sector.

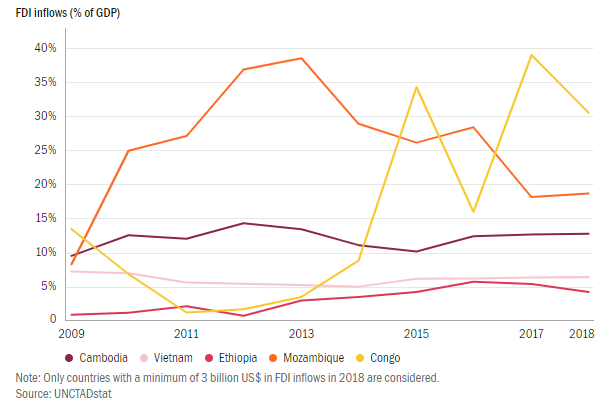

Figure 2: Top five developing countries most dependent on FDI inflows

The chart only depicts two African countries that are highly dependent on FDI and whose FDI inflows are concentrated in extractive industries — Congo and Mozambique — but there are many more, including Chad, Gabon, Guinea and Liberia. They are not depicted in the figure because, in absolute terms, their FDI inflows are lower than the cut-off point.

The consequences of FDI contraction (and resumption) for developing countries

Making predictions about the economic consequences of COVID-19 is a thankless task. We do not know how quickly economic activities will resume, we cannot yet determine the scale of the damage from the fall in global demand and supply, and we cannot envisage the nature of potential future fiscal stimulus packages.

Comparing recent data on business confidence in China and the United States — two countries that have an important impact on global investment flows — might give us a hint though as to the future of global investment flows. From the chart below, we see that China is following a different trend compared to the United States: business confidence in China is improving towards pre-pandemic levels.

Figure 3: Business confidence in China compared to the United States

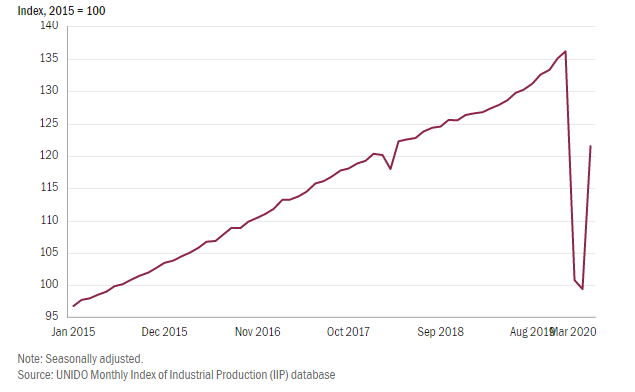

What does this mean? At the most obvious level, it means that China is resuming production and work earlier than other countries (business confidence in most other countries are showing trends similar to the United States). Monthly production data in China confirms this trend, as we see that manufacturing output rebounded sharply in March.

Figure 4: Manufacturing production in China

Taken together, this could indicate that we are seeing the start of a global V-shaped recovery of business activity, and that, assuming other countries’ recoveries, the global slump in FDI will not be as dire as predicted by some people. Or, it could indicate that Chinese companies are using this crisis as an opportunity for further expanding their global influence. In fact, FDI outflows from the Global South, primarily China, has been on the rise for a number of years now (UNCTAD, 2017). So it is not unthinkable that this pandemic will influence the composition of global FDI flows in the future.

It should be borne in mind, however, that the measure we are using here to indicate business confidence in China, the Purchasing Managers Index (PMI), has been subject to scrutiny (Powell and Jones, 2020). Yet more importantly, the PMI reflects a trend, and that trend reveals that levels of production are improving, and not that they have returned to pre-pandemic levels. Additionally, due to the nature of FDI, we should be prepared for a slow recovery. In many instances, cross-border business ties need to be re-established; investors are normally more risk averse abroad than at home, and there are a number of complicated operations and logistics challenges involved in restarting production in a foreign country.

If the contraction in global FDI lasts for a while, the consequences for developing countries will be severe. It will impact them in different ways, however. Countries whose extractive sectors depend on FDI inflows, many of which are in Africa, will first and foremost experience a loss in export revenues (which many already have due to the plunge in prices for primary commodities, especially oil ). The consequences of a global contraction in FDI could be even more serious for developing countries with a more diversified portfolio of FDI inflows, because the potential benefits of such inflows are greater: FDI inflows do not only boost export revenues in these countries, they also boost employment, tend to have a more positive impact on infrastructure development, and can result in technology transfers to the host economy, particularly in the manufacturing sector (Hauge, 2019). In addition to a loss of investments, we can expect many investors to halt their plans for expansion. Attracting investors is only the first step towards a successful FDI strategy. Convincing investors to stay and expand their operations is a key factor for achieving economic development goals.

Policy efforts to mitigate the negative effects of FDI contraction

To recover post-COVID-19, the world—and developing countries in particular—will require a significant influx of resources. FDI inflows can bring in some of those resources, but governments will need to put conditions in place to help attract and retain productive investments and, more importantly, to maximize their development benefits. This crisis may offer a window of opportunity for governments to re-examine their approaches to investment attraction and retention, with a view towards increasing the embeddedness of FDI within their local economies. To this end, we highlight three focal areas that may require novel policy approaches and thus deserve increased attention from policymakers:

First, measures and supportive mechanisms to help local firms overcome supply-side constraints must be introduced and further strengthened. Two types of measures specifically can be fruitful in the longer term in this respect, both for developing stronger linkages between local and foreign firms, as well as to improve competitiveness of local industrial structures: the development of a system of quality certification that is often required to enter into the supply chains of foreign firms, and improvements in digital infrastructure that allow firms to operate remotely both along global value chains and in reaching out to foreign markets.

Second, export processing zones (EPZs), which have been an important tool for attracting FDI in many developing countries, should be designed in a way to link up to the domestic economy. This calls for EPZ regulations that support the establishment of local supplier relationships, including the design of supplier development programmes to support match-making processes between foreign firms and local suppliers.

Third, international actions to support countries during and after the pandemic need to pay particular attention to least developed countries. Those countries are facing particularly hard budget constraints and are often limited to implementing policies that focus primarily on investment facilitation measures, simply because they do not have the resources to offer more substantive support to their private sector firms (UNCTAD, 2020). This is why it is crucial for international organizations and country groupings, like the United Nations and the G20, to respond to their calls for support by advocating and facilitating cooperation in the area of international investment and trade policy.

Originally published on May 22, 2020 on UNIDO’s Industrial Analytics Platform (IAP), a digital knowledge platform that combines expert analysis, data visualizations and storytelling on topics of relevance to industrial development. Other articles published by UNIDO’s IAP can be found here.

Written by

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect WAIPA’s stance.